January 30, 2018

This is an adapted version of my presentation at the European Council on Foreign Relations’ Conference in Warsaw, drawing on experiences from the Arab Spring and Asia:

I am grateful for the invitation to speak about democracy and the rule of law in Myanmar. I have worked as a defense attorney in the States and also have served my time as a divorce lawyer johnson county, and so, have had adequate experience in dealing with the law. Let me begin with the broader context: Of all the uprisings, I have witnessed in Asia demanding government change and even democracy, only one has had some success in achieving democracy and creating Rule of Law.

The Burmese students tragically failed in 1988, their Chinese peers did likewise in 1989, although some of their demands were met in a circumspect way the following many years. Even if they still have considerable challenges, the Mongolians succeeded in 1990. No such luck for democracy activists in Bangkok during the brief Bloody May in 1992. And the UN’s efforts to democratise Cambodia in the early 1990s failed miserably, and even now 25 years after the first free and fair general election, the Cambodians suffer from corrupt and oppressive authoritarian government, with a ‘strong man’ who manipulates elections and refuses to honour the popular vote.

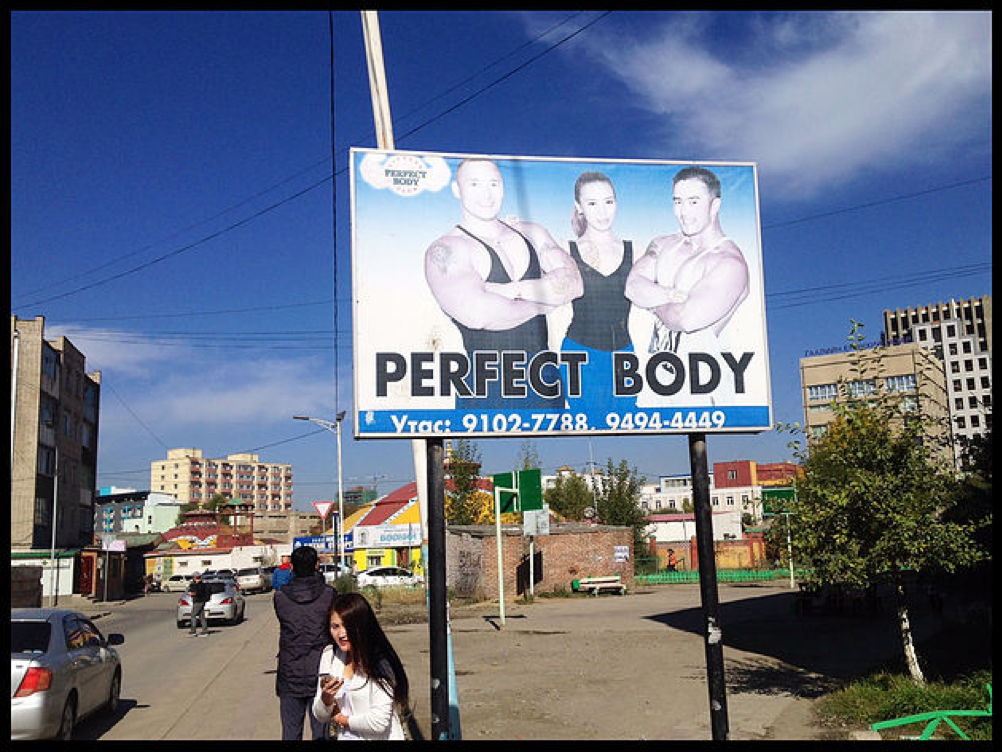

Mongolia’s democratic revolution has been the most successful by far, and led to a democratic multi-party system, market economy as well as gradual approximation towards rule of law. The 13 students who led the peaceful revolution in Ulaan Bataar in 1990 in minus 40 degrees Celsius, continued in civil society and in politics, some continued as activists, others became political leaders, MPs, government ministers, mayors. Ts. Elbegdorj became his country’s president for two terms, 2009-2017. There are still many challenges, not least poverty and corruption, but there is also a clear sense of identifying and having to avoid the undemocratic backlashes and pitfalls that many of the former soviet-dominated countries have suffered, e.g. Ukraine.

While both the Burmese and the Chinese students payed dearly for their demands for democracy, they have taken some consolation from the belief that their failed attempts inspired a wave of democratic uprisings in the late 1980s and early -90s; but in Mongolia the leaders of the revolution say they never looked south, rather they were inspired by developments in Eastern Europe and the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Beijing Spring

The 1989 uprising in China started with Beijing university students’ relatively modest demands for influence and the right to create an independent students’ organisation; the protests soon swelled into the biggest challenge ever of China’s Communist Party’s leadership. Millions of Chinese demonstrated against corruption in the Communist Party and for increased influence in their own lives. The uprising was brutally crushed by the government and the People’s Liberation Army. Hundreds of demonstrators were killed, thousands were imprisoned, others simply disappeared, while many more were sent to the countryside for a year or two to ‘learn from the peasants’.

Albeit the Chinese leadership will never admit to having so much as listened to the demonstrators in 1989, one can argue that some of the demands were gradually met over the years. Even if they have tightened their grip on power, which they will never voluntarily relinquish, the Chinese leaders have since made certain to improve living conditions, opportunities, choices in many aspects of life and the market, and even the possibilities of expression although it is nowhere near actual freedom of expression.

Thus, the majority of the Chinese have experienced considerable improvements in their lives and opportunities since the uprising in Beijing and other major Chinese cities in 1989. And even if every Chinese leader since then has pledged to combat corruption, none have succeeded. And it’s hard to determine whether the present party boss (and president), Xi Jinping’s energetic efforts to eliminate corruption are directed at corruption per se or simply at getting rid of political competitors.

8888 Uprising in Myanmar

One year earlier, in Myanmar, Burmese students and other frustrated citizens, fed up with repression, poverty, backwardness and isolation, started massive protests that topped on August 8, thus named 8888, and failed, in September 1988. As many as 10 000 people, both protestors, soldiers and anyone who came in the way of the army, perished during and in the wake of the protests, when the military junta struck back with immense force. Schools and universities were closed, thousands were arrested and imprisoned, students fled country entirely or went to Thailand and the border region to take up arms.

Bloody May

In Bangkok 200 000 democracy activists took to the streets in May 1992 to protest Suchinda Kraprayoons government, only to be met by a brutal military crackdown. An eerie quiet and smoking burnt out cars, belly up, had replaced the usual traffic jam. I saw human flesh stuck to a tree trunk, where protesters had been shot. At least 50 people were killed, hundreds injured and thousands arrested and tortured. And democracy still seems distant in Thailand.

Miserable failure in Cambodia

In the case of Cambodia, the people were never really heard. The Cambodians have suffered immensely and lived – and many, many have died – through the civil war, under the brutal rule of Pol Pot and his Khmer Rouge army, and since 1979 in one shape or other under the increasingly oppressive and corrupt rule of Hun Sen and his Cambodian People’s Party, the former communist party. Lord Prime Minister, Supreme Military Commander Hun Sen is a former Khmer Rouge Officer and one of the world’s longest serving leaders.

Democracy was introduced by the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia in the early 1990s at great pains, with sincere volunteers braving rivers and mountains in canoes and on elephants to inform the battered Cambodians of their democratic right to vote; democratisation proved much more difficult than anticipated, and despite the country formally being a democratic constitutional monarchy, and Cambodia being party to any and every relevant UN Convention, the Cambodians have yet to actually experience democracy.

The Myanmar Experience

Oh, Myanmar … Hopes were high and expectations even more so, when Aung San Suu Kyi was finally allowed to actively engage in Myanmar politics in 2012 – as an MP and since 2016 as her country’s de facto leader.

A summary is appropriate here: Burma – Myanmar – was a malignant military dictatorship for 50 years. A military coup in in 1962 strangled this rice bowl of Asia, this exporting nation, a regional trade and traffic hub, and for good measure a democracy as well! The beautiful country sank into terror, deep poverty, backwardness and ethnic strife.

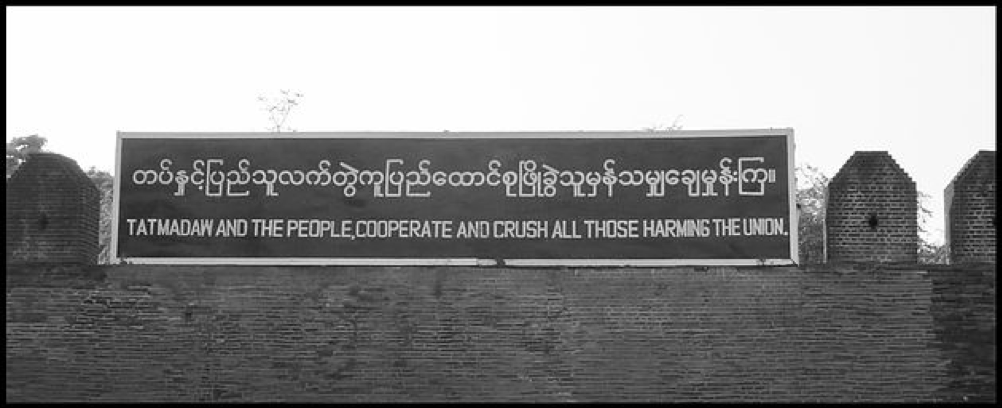

The generals’ aim was to cling to power, keep the Tatmadaw (the armed forces) ship-shape and safeguard the Union of Myanmar – all 14 region-states and all 135 ethnic groups – except, of course, the Rohingya of Rakhine (formerly Arakan) State.

© Mette Holm

The Burmese had no – or very little – say. When they have protested over difficult circumstances, e.g. over price hikes, currency reform that left whatever money they had worthless, useless health and education systems, mostly they have been severely punished, thrown in prison far from family and care, or worse.

The 1988 students’ uprising resulting in thousands of deaths, many more arrests and incarcerations, and huge waves of refugees to Thailand and further afield – this was both frustration over incompetent government, lack of all basic goods and services – and demands for democracy.

The protests shocked, angered and frightened the generals, and led to even worse conditions, killings, persecution, closing of educational institutions, more forceful political suppression etc.

A surprisingly free and fair general election took place in 1990 which gave the leader of the opposition Aung San Suu Kyi an overwhelming victory, even when she was in house arrest. The generals had not anticipated that they would be outvoted, so they simply ignored the result, dissolved entire villages where people had voted ‘incorrectly’, and gave these voters a chance to vote once more, this time ‘correctly, i.e. for the generals. Universities closed for years, and when eventually reopening relocated to remote and inaccessible areas.

In 2007, the Burmese experienced what they perceived as yet another ambush from the government with huge price hikes and a further incomprehensible decrease in living conditions. This time the revered monks took to the streets because what little, people had left to live on was taken away from them. Ever since the military coup in 1962, people have turned to the Buddhist temples for solace, guidance and education, and other services which a state would normally take care of. People marched in front, alongside and behind the monks to protect them from the Tatmadaw. The army attacked the people once more, people were killed, this time even the monks. The government’s handling of what became known as the Saffron Revolution was widely communicated via mobile phone video recordings, and harshly criticised abroad.

The generals sensed something rotten

The generals had sensed for a while that something was rotten. They had very few friends in the global community, North Korea being one. China was very close too, but couldn’t exactly be termed a friend. The generals sold China all sorts of raw materials and rights, to build dams to secure water supply in Southern China, passage to the Indian Ocean, oil and gas as well as mining rights, whatever China wanted, the generals sold for personal gain. The people of Myanmar were very much against this, but had no say. From a strategic point of view, some of the soberer minded and less corrupt generals were uncomfortable with China’s large and increasing influence over important infrastructure.

Also, they moved the capital from Yangon to Nay Pyi Daw in the middle of nowhere, partly to avoid new popular protests around government institutions, partly out of paranoia and the fear of being attacked by foreign powers from the sea. Also, Aung San Suu Kyi became an ever-increasing embarrassment in her house arrest in Yangon.

Or it may have been Saddam Hussein’s violent demise and death in 2003 that gave the generals second thoughts – whatever it was, all on their own, shrouded in secrecy, they wrote a new constitution, published it in April 2008 and demanded that all citizens buy and read it; at 1000 kyats it was much too expensive for most people. A referendum was to take place a month later.

Three weeks later the Southern part of Myanmar was hit by a devastating cyclone, Nargis which killed almost 140 000 people. The generals insisted that the referendum on the constitution take place as planned, and claimed that 98% of the Burmese were all for it – likely also some of the victims of Nargis – and slowly started to dismantle military rule …

Shortcut from Military Dictatorship to Democracy?

This leads to an interesting question: is it possible for a military dictatorship – or any other form of dictatorship for that matter – to peacefully dismantle itself and evolve into a democracy?

Rulers who use their power to supress and terrorise people, sensibly fear for the day when they are no longer in power. What will people do? Will they take revenge? Look at Saddam Hussein, look at Muammar Gaddafi! With no rule of law in place courts are no to be trusted. Also, the Burmese generals may have looked to Indonesia when deciding to gradually move towards some deviant of democracy.

After Suharto’s resignation in the late 1990es, Indonesia has seen a strengthening of democratic processes and institutions, amongst them direct election of the president (since 2004)

The generals took a lot of precautions in their new ‘democratic’ constitution. 25% of the seats in the bicameral parliament are reserved for serving military officers. So only 75% is open to popular vote. This means that it is well-nigh impossible to decide anything without the support of the army.

Also, the generals went to great lengths to prevent Aung San Suu Kyi from becoming president – because she had been married to a foreigner, had two sons with him, and these two sons carry foreign citizenship. However, this was circumvented after the 2015 general election, where a loyal member of Aung San Suu Kyi’s party The National League for Democracy (!) became president, while she became the first 1st State Counsellor of Myanmar with much the same power as a president as well as that of a prime minister. Further to this, she is, of course foreign minister.

1st State Counsellor

Daughter of the independence hero and founder of Myanmar’s military, Bogyoke Aung San, Aung San Suu Kyi is of prime Burmese political aristocracy.

While she spent the better part of her life since 1989 in house arrest as a political prisoner, the generals were acutely aware of her pedigree, as was she herself. Also, she became the beacon of hope for Myanmar’s terrorised people because of her unwavering opposition to the military junta.

Her unique status meant that when pondering their own future, the generals very much had to consider hers as well. Aung San Suu Kyi was – and is – the only person who can protect the generals from the wrath and revenge of the Burmese people. We don’t know what deals they might have made, but Aung San Suu Kyi never made a secret of her ‘fondness’ of the army and sense of duty to her father – and her country.

An overwhelming majority of the Burmese people adored and had great faith in Aung San Suu Kyi when she was in house arrest and had no political power or position.

Icon of Freedom

When, in 1992, I visited an 85 km stretch of refugee camps between Cox’s Bazar and Teknaf in Bangladesh, housing a quarter of a million Rohingya who’d fled persecution and abuse in neighbouring Myanmar’s Rakhine State, everyone I talked to wanted the generals to turn over power to Aung San Suu Kyi who had overwhelmingly won the free and fair elections only two years previously.

Aung San Suu Kyi was admired and respected for her stubborn, peaceful struggle against the junta, at home and in the West.

I visited her in her home in 1995, during a short break in her house arrest, and witnessed the heart-warming gathering of thousands of Burmese in front of her gate at University Avenue; many had travelled from afar to listen to her words on freedom and human rights and how she had no intention of spending the money from her 1991 Nobel Peace Prize until Burma (as she calls her country with the former British name) and all the Burmese were free to enjoy it.

During the week people placed paper slips with questions in in the mail box on the gate, and during the weekends she would climb a rickety ladder inside her courtyard, lean on the gate and answer the questions. The rapport between The Lady and her followers was warm, humorous and encouraging. This was before the social media; people recorded her speeches, copied the cassette tapes and brought them home to the villages to spread the word.

When, some 15 years later, she finally won her freedom and political power, she was met with high hopes and great expectations …

Although the political party she founded is called The National League for Democracy, Aung San Suu Kyi never really promised democracy, she certainly never practised it in her own party. Human rights, perhaps, but not democracy.

The first days of ‘civilian’ government from 2011-2016 were euphoric, an explosion of expression, in art, media, social media, promises of rule of law to replace the old legislation, some of which dated back to British colonial rule – and sadly, still does.

Corruption is still – or once more – rife. Poverty too. Development has not reached remote areas, ethnic strife has resurfaced, and one group in particular has been singled out for persecution yet again by Myanmar, described by the UN as a ‘school book example of ethnic cleansing’ and possible genocide.

The Intolerable Plight of the Rohingya

The Rohingya people inhabited what is now Rakhine state as early as the 15th century and were later imported by British colonial rule as cheap labour from what was then Bengal, part of British India. They have lived for generations in Rakhine State in Myanmar.

After the military coup in 1962 some half a million Burmese of Indian origin were stripped of their citizenship and forced ‘home’ to India. Military campaigns were launched against the Rohingya to force them ‘home’ as well – but by then, British Bengal had become East Pakistan, which did not consider them compatriots.

Persecution continued on a regular basis, and in the late 1970es large numbers fled to what was now Bangladesh. The UN negotiated their return to Burma, in 1992 they fled brutalisation, expulsion off their land, rape and murder once more, and were yet again repatriated. All along, Burmese military has routinely confiscated and destroyed birth certificates and land leases, without which Rohingya people cannot prove their right of birth and land.

Now, once more, Rohingya refugees throng in totally inadequate camps along the road between Cox’s Bazar and Teknaf, this time 650.000. The most recent wave of persecution and brutalisation of the Rohingya started in 2012 and was vastly amplified by the new freedom of expression in the social media. A country of some 60 mill. people, who for decades have been allowed only very restricted and censored access to news in the shape of glaring government propaganda, a few TV-channels, a tiny number of radio channels and a single newspaper, New Light of Myanmar, was – and is – incredibly vulnerable to propaganda.

And then, from one day to the next, new media and new ways of communicating; a Buddhist monk, a representative of a most revered group in society, telling the mainly Buddhist and mainly Burman Burmese, some 90% of the population that the Muslim Rohingya in Rakhine State want to take over the entire country. People were easy prey to this new kind of propadanga to stigmatise and persecute the Rohingya and soon Muslims in general as well

This was the moment for Aung San Suu Kyi to have seized, May 2012, when the first clashes between Buddhist Rakhine and Muslim Rohingya exploded in the burning down of Rohingya villages, seizing of property and killing of people … The until now strictly controlled police and army had no orders on how to react, and mostly just stood by. Mosques and madrassas were burnt to the ground, the killings continued.

Former general and prime minister in the junta and president in the first ‘civilian’ government, Thein Sein, actually approached Aung San Suu Kyi for the two of them together, the two Burmese, Buddhist Burman with the largest moral authority and capital in the country at the time, to join forces and stop the madness, impress on the Burmese that the situation was unacceptable, this was no way to handle disagreement and contradictions, stop the confrontations and killings, separate the parties, investigate thoroughly and restore order – and prosecute the criminals … Old laws too, safeguard the unity of the Union, they would have been appropriate to solve and settle the problem.

Incapable government turns blind eye

Aung San Suu Kyi refused to comment and spoke bleakly about ‘human rights’ not wanting even to mention the Rohingya by name. She castigates the international community for using the term Rohingya, which is how they wish to be known, and accuses the UN of being behind attacks on security posts by the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army – a small, new I believe, and ill organised resistance movement. She bases her grave accusation on the fact that biscuit wrappings from UN emergency rations were found in the ARSA camp.

The Myanmar government either refuses to or is incapable of coming up with a sustainable solution to the Rohingya problem. A recent deal to repatriate the Rohingya in Bangladesh has no guarantees for decent treatment and protection when they return to Myanmar, which refuses to let in international observers.

The Aung San Suu Kyi government has been unable to deliver on the hopes that brought her to power. Other grave and unsolved ethnic, political, economic and development issues block the way for strong institutions and development in general; this again frightens off much needed foreign investment to drive modernisation of a hugely backward and poor country, creating a vicious reactionary circle – exactly the opposite of the enthusiastic optimism of the introduction of ‘civilian’ rule, when hopes for democracy and human rights were high in Myanmar after 50 years of brutal military rule.